Roadblocks to Competition: Investigate Google’s Non-Compliance with the EU’s Digital Markets Act

Today, we are calling on the European Commission to launch three non-compliance investigations around Google’s obligations under the EU’s Digital Markets Act (DMA):

- On Google’s non-compliance with Article 6(11), which requires Google to share anonymized click and query data.

- On Google’s non-compliance with Article 6(3), which requires Google to implement choice screens and enable end users to easily change default search settings.

- On Google’s non-compliance with Article 6(4), which requires any downloaded search or browser app to have the ability to prompt users to set search defaults easily.

The DMA created these obligations to address Google’s scale and distribution advantages, which the judge in the United States v. Google search case found to be illegal. The judge specifically highlighted that 70% of queries flow through search engine access points preloaded with Google, which creates a “perpetual scale and quality deficit” for rivals that locks in Google’s position.

Unfortunately, Google is using a malicious compliance playbook to undercut the DMA. Google has selectively adhered to certain obligations – often due to pressure from the Commission – while totally disregarding others or making farcical compliance proposals that could never have the desired impact. As a result, the DMA has yet to achieve its full potential, the search market in the EU has seen little movement, and we believe launching formal investigations is the only way to force Google into compliance. The Commission has already demonstrated its ability to use such investigations effectively under the DMA.

While Google’s bad faith approach is not surprising, it should not go unnoticed. Any regulator looking to create enduring competition in the search market should take note of the tactics Google is using to thwart and circumvent its legal obligations.

We project Google’s Click-and-Query data sharing proposal eliminates ~99% of search queries.

Google’s exclusive default distribution deals mean they see many times more search queries than any competitor can, which gives them what’s called a “scale advantage.” In Article 6(11), the DMA directly addresses this scale advantage by mandating Google share anonymized click, query, ranking, and view data. This data would help search engines improve results quality, especially for less frequent (so-called “long-tail”) queries.

Google’s Click-and-Query obligation under the DMA, Article 6(11), reads:

“The gatekeeper shall provide to any third-party undertaking providing online search engines, at its request, with access on fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory [FRAND] terms to ranking, query, click and view data in relation to free and paid search generated by end users on its online search engines. Any such query, click and view data that constitutes personal data shall be anonymised.”

To comply with this requirement, Google announced the “Google European Search Dataset Licensing Program.” However, this data set has little to no utility to competing search engines due, in large part, to Google’s proposed anonymization method, which only includes data from queries that have been searched more than 30 times in the last 13 months by 30 separate signed in users. This method is conveniently overbroad: we extrapolate that Google’s dataset would omit a staggering ~99% of search queries including “longtail” queries that are the most valuable to competitors. Google is trying to avoid its legal obligation in the name of privacy, which is ironic coming from the Internet’s biggest tracker.

Part of our goal at DuckDuckGo has always been to prove that tech can make great products without exploiting people’s data or using mass surveillance. Our Privacy Policy explains how we go about doing this, for example, “we have no way to create a history of your search queries.” We do this by stripping out any metadata that can tie searches together made by the same individual, so re-identification cannot happen like in the memorable AOL case. For example, we may know that we got a lot of searches for "cute cat pictures" today, but we don’t know - and have no way to figure out - who actually performed those searches.

The fact is that most "rare" queries are actually just common words put in an order that isn’t searched very often. These queries are not inherently problematic since they cannot be traced back to any individual. So, instead of attempting to filter all of these relatively unique queries, we should instead focus on removing the subset of those queries that contain personal identifiers, like addresses and phone numbers or accidental pastes like user ids and passwords. Fortunately, there are relatively straightforward approaches to remove these types of queries that will result in much of the long tail data remaining available to improve search results.

This isn’t even the only part of the proposal that severely hampers the usefulness of the data:

- The proposal averages ranking data, which eliminates critical nuances. It also doesn’t provide anonymous ranking signals like dwell time or bounce rate.

- The proposal shares at best three-month old data, meaning the data is already stale when received because many results would no longer reflect current search trends.

- The proposal contains hardly any information on search modules, such as knowledge panel content, meaning information on much of the content on the search result page is not being shared.

We recognize that fine-tuning the right approach requires further considerations and, most importantly, testing and good faith cooperation from Google. Faced with Google’s continued obstruction, we believe that opening an official investigation is the only way to arrive at a workable proposal. We would like to help in that effort and believe there are ways for Google to provide a data set that is both privacy respecting and useful to competitors.

Google has so far completely ignored “easy switching” requirements.

The DMA includes provisions designed to facilitate easy switching of search engines and browsers, targeting Google’s entrenched hold over search and browser access points. Google’s obligation under Article 6(3) of the DMA reads:

“The gatekeeper shall allow and technically enable end users to easily change default settings on the operating system, virtual assistant and web browser of the gatekeeper.”

Despite this obligation, switching search engines on Android devices (which make up more than 60% of the mobile market in the EU) is still not “easy.” Before the DMA came into effect, it took more than 15 steps to switch your default search engine on Android and today that is still the case.

Zero changes have been made. What should happen is that users should be able to change their default search engine across every search access point in one click, similar to how a choice screen works, but currently choice screens are only shown on device onboarding. Users should be able to get back to a similar screen via a top-level device setting for default search, which we should be also able to guide users to directly from our app.

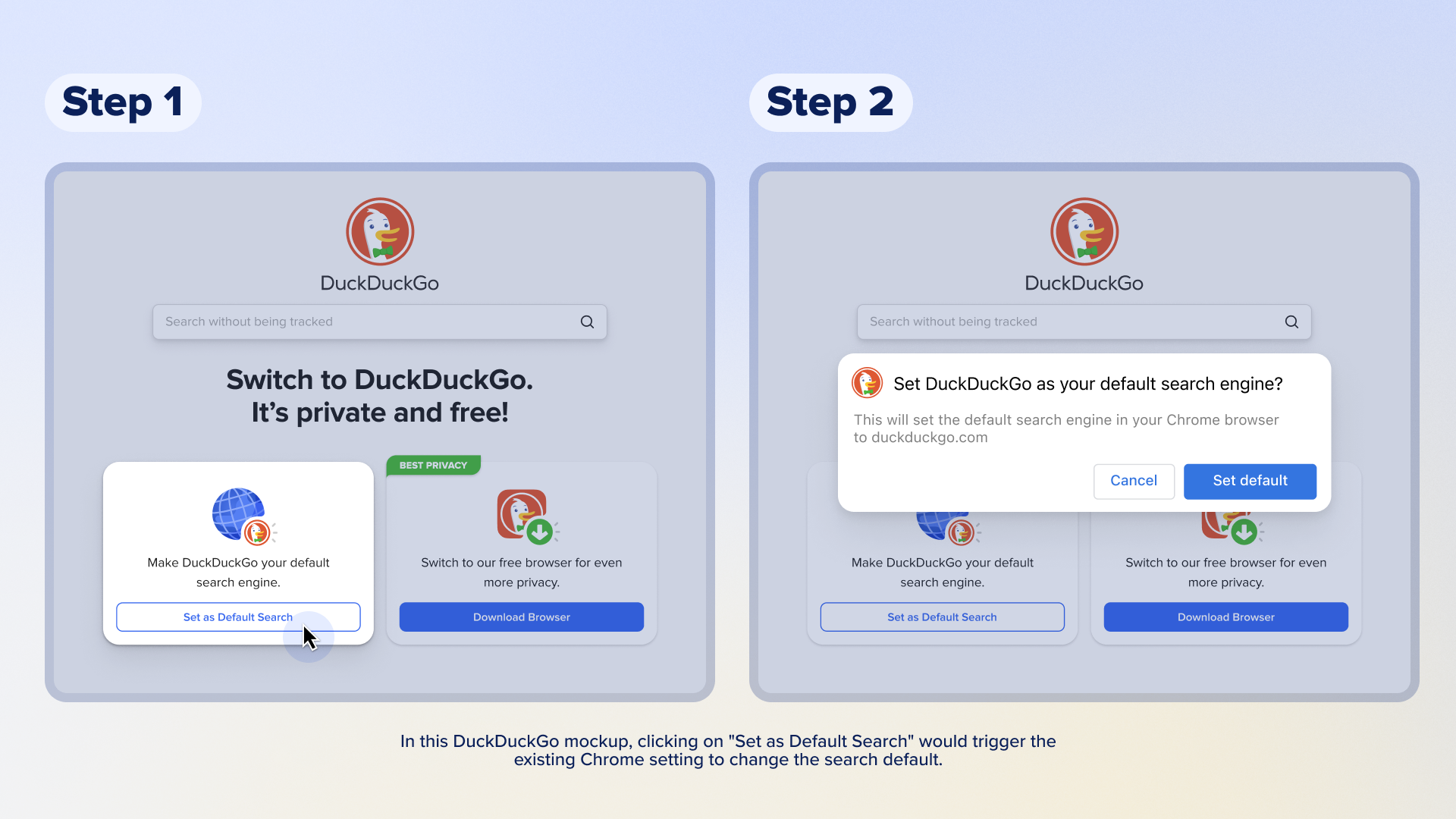

Similarly on Chrome, switching the default search engine has not been made any easier either. For example, there’s still no way to guide a user directly to the default search engine setting from the DuckDuckGo search homepage. And Google’s persistent dark pattern for search extensions on Chrome remains.

Google has completely ignored its easy switching obligations under the DMA. As a result, we believe the Commission must launch a non-compliance investigation to get Google to fulfill its requirements under the law. “Easy switching” should mean competition is actually one click away.

Google still hasn’t rolled out its updated Android choice screens to 250+ million EU Android users.

Article 6(3) DMA requires Google to show choice screens to end users “at the moment of the end users’ first use of an online search engine or web browser.”

Google’s search engine DMA choice screen is explicitly different from the choice screen Google implemented following the Android case. Key improvements have been made to its design, such as automatically showing taglines. But Google has not rolled out this updated DMA choice screen to all Android users, in breach of Article 6(3). Apple, for example, rolled out its DMA browser choice screen to its entire EEA user base and is planning to do so again after an investigation from the Commission – this time to Safari default users only.

A non-compliance investigation must therefore be opened to ensure that Google will fulfill its obligation and roll out both the DMA search engine and browser choice screens to all Android devices at once like they did on Chrome for desktop and iOS. When those Chrome choice screens rolled out, the positive competitive impact was evident: DuckDuckGo search queries on Chrome have increased by around 75% across the EEA. This rapid and stable growth in query volume shows pent-up demand by Chrome users for privacy-respecting search alternatives.

What can regulators learn from this?

Regulators around the world should be looking at what’s happening with the DMA, learn from how Google has been able to exploit its loopholes and circumvent it, and then take steps to make sure Google cannot continue to put up roadblocks in the way of progress and fair competition.

In the EU, Google chose to roll out self-serving compliance proposals around these obligations without engaging in meaningful consultations, leading to significant delays in achieving contestability and fairness, the objectives of the DMA. Given the opportunity, it should not come as a surprise that Google is taking advantage.

Instead, regulators and market participants should be able to review, test, and validate remedies before they are implemented to ensure they actually accomplish their intended purpose, while maintaining the regulatory authority to launch investigations and make changes after implementation, if necessary. Regulators can set additional criteria to make sure these interventions have the desired impact. For example, dominant firms could be required to demonstrate that consumers understand how to switch and that switching to a competitor is equivalently easy to sticking with the services from the dominant firm.

In addition, we believe the DMA doesn’t properly address Google’s scale advantage. Sharing click-and-query data is a critical intervention to address Google’s scale advantage, but alone, it isn’t sufficient to create a competitive search engine. As we’ve previously written, we believe the best and fastest way to level the playing field on search quality is for Google to provide access to its search results via real-time APIs (Application Programming Interfaces), also on FRAND (Fair, Reasonable, and Non-Discriminatory) terms. That means for any query that could go in a search engine, a competitor would have access to the same search results.

If Google is required to license its search results in this manner, this would allow existing search engines and potential market entrants to build on top of Google’s various modules and indexes, and offer consumers more competitive and innovative alternatives. In addition, while choice screens are an excellent mechanism to provide consumers access to competitors, they need to be shown periodically, at least yearly, to give competing search engines a chance to build awareness over time. We are happy to work with regulators to craft remedies that will create enduring search competition.